I saw my neighbor, Dreama, at the community cafe this morning. Dreama is an organist. She teaches organ and provides music for Sunday worship at a local church. Dreama is an artist who is passionate about her art. Something she said about being an organist intrigues me.

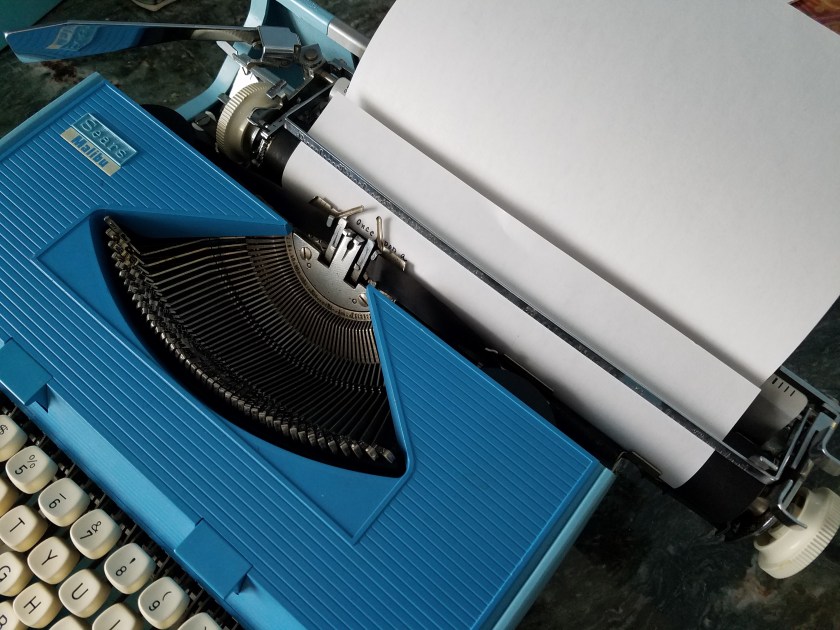

“We organists are a peculiar group. We love our instrument—the organ—but we can’t take our favorite organ with us when we go out to share our work. We have particular organs we love to play, but we can only play them in the place where they live. Organs are not really transportable.”

Thank you, Dreama, for inviting me to think about how important it is that people in all professions pay careful attention to the places where we do our work. Having a “sense of place” is vital to the effectiveness of our professional endeavors. It is also vital to the life and health of the communities where we hang out our shingles, if you will, as artists, doctors, lawyers, teachers, ministers, and others.

What is a “sense of place”? Some people say a locale’s “sense of place” is shaped by the characteristics that make it unique from other locales. People are drawn to these characteristics and are connected to places over a lifetime because of experiences they have in them, whether good or bad. Communities cultivate a healthy “sense of place” when they instill in their residents an authentic sense of belonging. And an authentic sense of belonging can heal broken hearts, foster peace and inspire hope, and lead to overall communal well-being.

Dreama, as an organist, has had to cultivate an awareness of place as vital to her artistry. She plays organs in diverse locales. Each organ in each locale is unique, designed by a particular builder and then constructed, in part on site, to fit the architecture and acoustics and sometimes oddities of the space.

Author Agnes Armstrong specializes in the history of 19th Century organists and organ music. She writes that

in medieval times, a builder would move his workers and often his entire family to the site of his next organ. They might even take up residence inside the cathedral being built around them, sometimes for a year or more. There they would be devotedly occupied with building the organ. . .

Agnes Armstrong

Organs, especially pipe organs, become a part of a place’s architecture.

Organs also hold stories:

“I will never forget how I felt when I heard those first organ notes as I came down the aisle on my wedding day.”

A woman in a nursing home remembering her wedding

“I remember hearing all of Mama’s favorite pieces played on that organ for the prelude at her funeral.”

A family member’s recollection of a funeral service

Good organists develop their musical skills and expertise over their lifetimes. Amazing organists also attend to each organ’s peculiarity and to the stories, memories, and connections that are present when they sit down to accompany a choir or perform a concert.

I am grateful for the conversation with Dreama. She is an amazing organist. Her wisdom about her art reminded me to lean in to the places where I go as teacher, poet, and preacher to listen for all of the voices and stories that make a place what it is. The health and well-being of leaders and the communities we serve depends on a rich meeting or intermingling of our story and skills with the particular and peculiar stories, gifts, and challenges of the places where we serve.

Agnes Armstrong writes that “pipes in a newly constructed organ must ‘settle in’ and ‘make their own community’” within the space where they reside. We all do that when we bring our artistic and professional endeavors to a new place. Like pipe organs, we learn to breathe in and with our new communities, and in partnership with them to make music that is unique to us and that has the potential to make a difference in our world.